Jon Needs a New Plow

By the spring of 1971, the re-power business had really taken off and customers wanted to see the tractors work in the field, and one of the best ways to demonstrate the power was by pulling a plow. I had borrowed a seven-bottom John Deere plow, called a semi-mounted plow. It had a front wheel in the furrow and a tail wheel in the furrow. It was an on-land hitch so you simply hooked up to it and plowed. The problem with that type of plow was that it would plug up with trash underneath. It was very frustrating to go out and demonstrate how easily a tractor would pull that big plow, only to turn back and see it choked full of cornstalks. Vertical clearance was just a disaster on those plows.

So, out of desperation, I went looking to buy a better plow. One of my customers, Edgar Folkmann, had an Oliver plow. He had bought one of my re-powers secondhand, which is an interesting story. It was a tractor I had done for a Missouri farmer who had come into some insurance money and had gone on a spending spree. He had bought new tractors, new trucks, new pickups and new cars. A few months after I re-powered his brand new John Deere 5020, I got a call from him. He said, “Do you reckon you could sell that John Deere that you re-powered for me?” And I said, “Well, I suppose. But what’s the matter? Don’t you like it?” “Oh, Jon,” he said, “I love it. But Jon, I got my wants and my needs mixed up.” The way he said that, with his Southern drawl, was a statement that I’ve never forgotten. So I sold his tractor to Edgar Folkmann. Edgar had a seven-bottom Oliver plow, which had a little more vertical clearance under it. I decided to buy one and went to the Oliver dealer in Conroy, Iowa.

I told the owner, Ed Stanerson, that I wanted a seven-bottom plow. Ed asked, “Do you want the Speed X bottoms?” And I said, “Yes.” And he said, “Do you want the 20-inch coulters?” And I said, “Yes.” And he said, “We’ll have to order this plow. But it won’t take long to get it in. Now when it comes in,” he said, “do you want this set up as a 16-inch or an 18-inch cut?” And I said, “What do you mean?” “Well,” he said, “we can set it up either way.” I said, “Well, doesn’t it take a longer backbone, or longer mainframe, to make that a 7-18 versus a 7-16?” “No,” he said. “The holes are drilled and the bottoms go on at a different angle. The bigger the plow, the more you straighten out the angle.”

On Goes the Lightbulb

Well, the light bulb came on and I told Ed, “Let me think about that a while.” I understood plows — I’d adjusted them since I was 10 years old and had a knack for doing it just by sight. So I went home and was thinking about how we could make that plow adjustable. And then it occurred to me that if you put a tie-rod on it and made a parallelogram out of it, you could basically pivot this thing with a hydraulic cylinder. And within the next 24 hours, it occurred to me that this thing could be made infinitely adjustable. It could be 12, 13, 14, 14½, 17, 18, 20 or more inches.

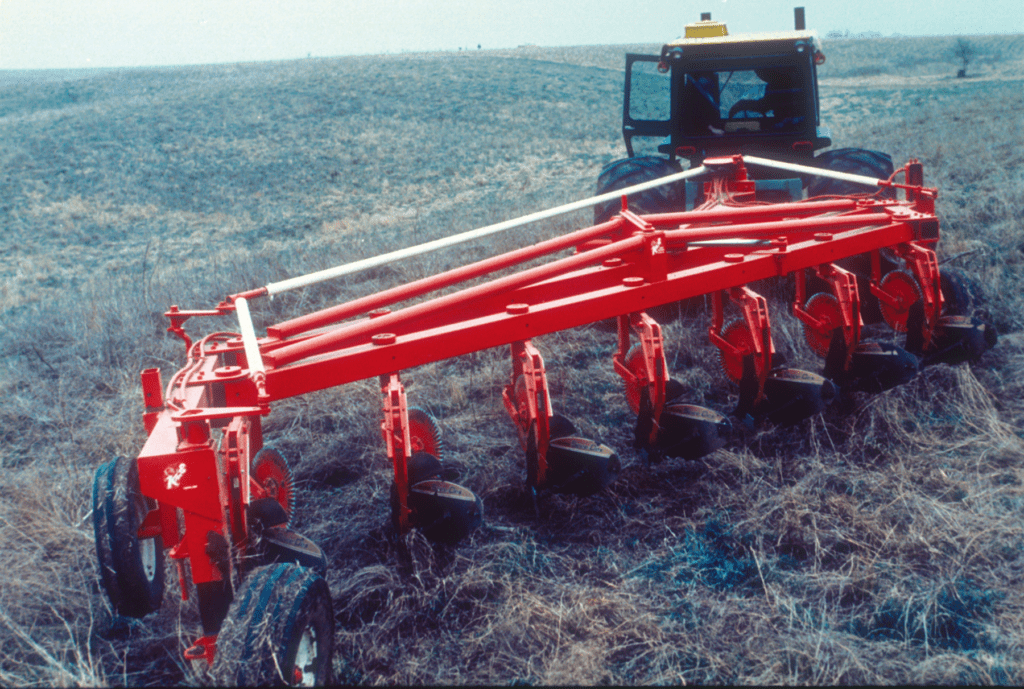

So I went back to Stanerson’s and bought seven new Speed X plow bottoms. Then I went to Cedar Rapids and picked up metal for the frame, and within 48 hours, I had this plow going together. I wasn’t exactly sure how it was all going to look, but in my mind I kind of knew where I was headed. We basically built that plow by drawing chalk lines on the floor and doing some squaring and adjusting. It was about midnight when the plow was finished, and we hooked it up to a brand new 5020 that I had re-powered. It seemed like everything we ever tested was done at midnight. It was probably a good time because there was a minimum of people around gawking and gaping at what you were doing lest you failed. But we — a couple of employees and two customers who had become good friends, Don and Dale Chilcote — got it hooked up and took that tractor and plow out to my dad’s. We pulled into the field about two o’clock in the morning and we plowed until we were satisfied it was going to work. Then we took it back to town and started cleaning it up. We got it painted over the next couple of days. On a Sunday afternoon in late March of 1971, we took it back out to my dad’s and plowed another sod field. A photographer, Lynn Beyer, took several pictures.

Building a Better Plow

The plow had enough vertical clearance that I could crouch down on my haunches and sit under the backbone. It was half again the vertical clearance of an ordinary plow. It could be adjusted, on-the-go, as far as 22 inches in width and as narrow as 12 inches. There were many advantages to an adjustable plow. First of all, you could match it to the width you wanted for the conditions. If you were cutting cornstalks and didn’t have any roots to kill, you could plow with it wider because it would pull easier. But if you were in alfalfa sod, you might take it down to 16 inches to allow the plow bottoms to cut everything off between the adjacent bottoms. But we had learned over the years that you don’t have to cut it all. You can roll it over, meaning you could have a four-inch gap from one bottom to the next and it would still roll the sod over.

The plow had enough vertical clearance that I could crouch down on my haunches and sit under the backbone. It was half again the vertical clearance of an ordinary plow. It could be adjusted, on-the-go, as far as 22 inches in width and as narrow as 12 inches. There were many advantages to an adjustable plow. First of all, you could match it to the width you wanted for the conditions. If you were cutting cornstalks and didn’t have any roots to kill, you could plow with it wider because it would pull easier. But if you were in alfalfa sod, you might take it down to 16 inches to allow the plow bottoms to cut everything off between the adjacent bottoms. But we had learned over the years that you don’t have to cut it all. You can roll it over, meaning you could have a four-inch gap from one bottom to the next and it would still roll the sod over.

After adjusting the plow for field conditions, the next thing would be to match the horsepower, by adjusting the seven-bottom plow bigger or smaller to fit your size of tractor. If you had a smaller tractor, you’d maybe pull it with the seven plows set at 14 inches. If you had a larger tractor on it, you could pull it at 20 inches. Damp or wet fields could also create a lot of traction problems. Therefore, when you narrowed it down, the traction was better. As you pulled it down the road, it pulled in nice and narrow and tucked in behind the tractor. Actually, it didn’t have to be adjustable; you could take the cylinder off and lock it forever at 16 inches or 18 inches. But it had better resale as adjustable, and we found that there wasn’t much difference in the cost, probably only $150-$200 more to make the plow an adjustable plow versus fixed.

The most important and difficult part of making the plow work properly was the parallelogram linkage that compensated for the angle of the tail wheel and oriented it properly to follow along in a furrow. Without it, the furrow would keep getting more crooked. That was something I hadn’t fully developed until I took the plow out to Bill Dietrich’s shop at DMI in Goodfield, Illinois. Bill helped me solve that problem by changing the linkage around.

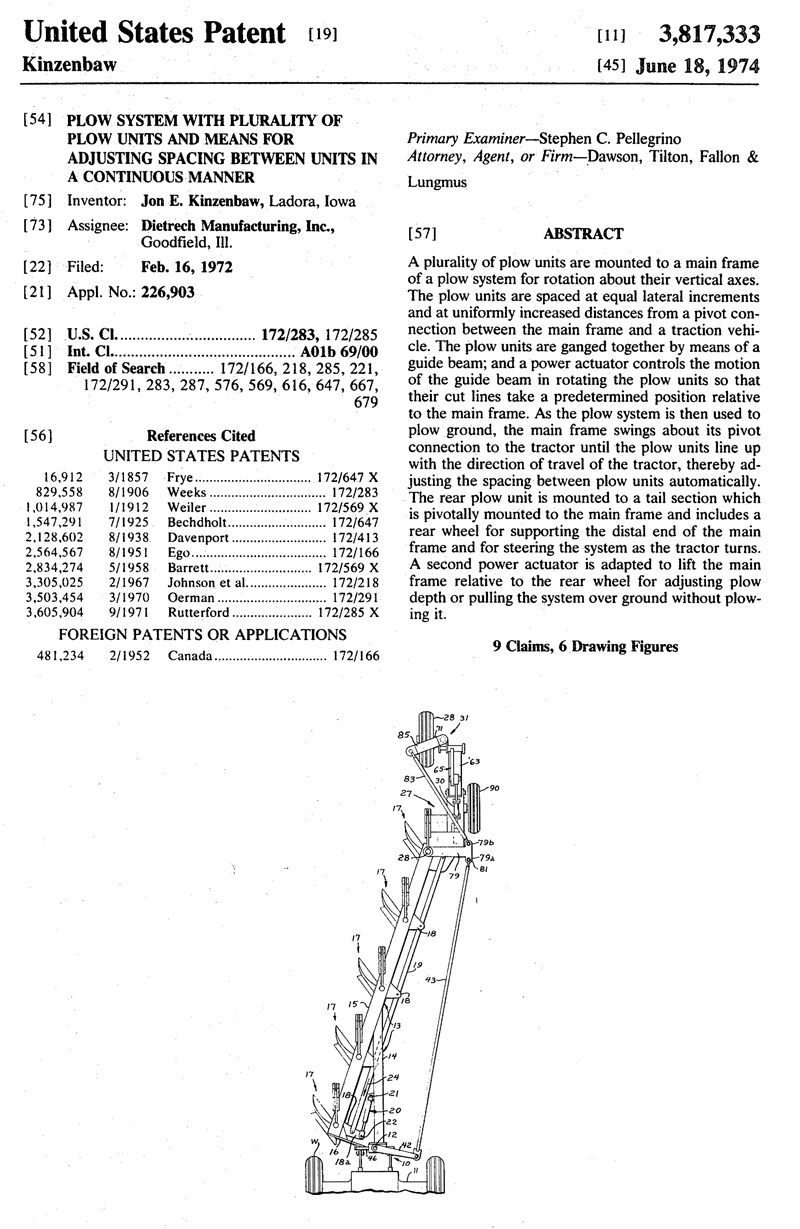

That plow made its first public appearance at the 1971 Farm Progress Show near Van Horne, Iowa, and there was a lot of interest in it. However, I could see that the plow would be expensive to promote and sell, so it made more sense to license it. So we licensed it first to DMI, then later on, to White Farm Equipment and International Harvester.

Getting the Patent

After I licensed the plow to DMI, I used Bill’s patent attorney, Jim Hill (who later became indispensable in the legal battle with John Deere). We filed the claims for patents on the plow, but Jim still wasn’t understanding what made it unique. So I finally took two toy plows apart and made a scale model of my plow and took it to Jim’s office in Chicago. I put it on his desk and showed him how it moved back and forth. Jim finally said, “My gosh, so that’s how that thing works!”

As we prepared for a trip to the Patent Office in Washington, D.C., Jim cautioned me. “You want to remember that most people who apply for a patent have an idea that they think is the best thing since sliced bread. They’re emotionally attached to their invention. But it has to stand on the merits. You simply explain it. If it’s a good idea and it has patentable qualities,” he said, “that will come through.” He said it was a rarity that the patent office allowed inventors to appear and explain their inventions, but in my case, he said, “They’re intrigued with this and they want to understand it. We’ll take this model and see if we can’t help them, because it’s obvious that I didn’t understand it until I saw the model.”

As we prepared for a trip to the Patent Office in Washington, D.C., Jim cautioned me. “You want to remember that most people who apply for a patent have an idea that they think is the best thing since sliced bread. They’re emotionally attached to their invention. But it has to stand on the merits. You simply explain it. If it’s a good idea and it has patentable qualities,” he said, “that will come through.” He said it was a rarity that the patent office allowed inventors to appear and explain their inventions, but in my case, he said, “They’re intrigued with this and they want to understand it. We’ll take this model and see if we can’t help them, because it’s obvious that I didn’t understand it until I saw the model.”

We got the patent, and within two or three years, Oliver, IH, John Deere and Kvernland in the Netherlands were breathing down our necks. They wanted that plow too.

Story Notes

The preceding story is an excerpt from Jon Kinzenbaw’s book, 50 Years of Disruptive Innovation, second printing, ©2021, Kinze Manufacturing, Inc.

A 12-bottom version of Jon’s adjustable-width plow is on permanent display at Kinze’s Innovation Center in Williamsburg, Iowa. Plan a trip to Kinze to see the plow, other Kinze innovations, and the factory for yourself.

Additional Information

Watch a 5020 with a 7-bottom adjustable-width plow operating in Kinze’s 50th Anniversary video (2015).

Purchase the book, 50 Years of Disruptive Innovation, for this story and many others about Jon’s early years and the growth of Kinze.

Purchase the children’s books, Big Blue & Polly and A Tractor & His Boy, and read the stories of some of Jon Kinzenbaw’s tractors to your children or grandchildren.